![]() Opposition

to immigration is largely cultural and psychological, and policy will have to address this, writes

Eric Kaufmann. He provides recent survey evidence that backs his argument, and explains why current policy-making seems to be based on the wrong assumptions.

Opposition

to immigration is largely cultural and psychological, and policy will have to address this, writes

Eric Kaufmann. He provides recent survey evidence that backs his argument, and explains why current policy-making seems to be based on the wrong assumptions.

The report of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee

Immigration Policy: basis for building consensus was released in January. It makes many helpful suggestions, including the idea of an annual migration report, streamlined immigration processing, and the importance of balancing competing interests.

However, it draws the wrong conclusions about public opinion and policy due to its reliance on focus-groups, which suffer from social desirability bias.

As a result, it makes two assumptions. First, that citizens who oppose immigration do so mainly because of their perceptions of its effects on prosperity or public services. If so, immigration is an issue that can be addressed by directing financial resources

to areas affected by migration, holding consultations, and communicating the economic contribution immigrants make. The second assumption is that voters are primarily concerned about control, not numbers. If they are reassured that things are under control,

and migration is being calibrated to economic needs, they will be content with higher numbers.

The report’s principal research base stems from polling and focus group work by

British Future which indicates that skills are the most important consideration for people when they think of a desirable immigrant. This gains support from a new

literature which uses survey experiments asking people to choose between two stylised immigrants who differ in either economic or cultural ways from each other. Across a wide variety

of different pairwise comparisons, analysts such as Jens Hainmuller and Dan Hopkins, using the conjoint technique, are able to

assess which aspects of an immigrant render them more or less desirable – whether they speak the language, whether they are European or non-European, Muslim or not, their skill level, employment and so forth. This work shows that national origin, religion

and race matter, but most respondents in most countries prioritise immigrants’

skill levels over ethno-cultural considerations. This seems to indicate that people are most interested in the economic contributions migrants can bring.

Yet, as behavioural economists repeatedly caution, ‘people aren’t rational, they rationalise.’ So too with immigration attitudes. The reasons people say they oppose immigration are those they are aware of, or feel to be socially acceptable. This is especially

the case in focus groups, where peer pressure is strong. Consider the Brexit vote. Leave voters told exit pollsters it was about sovereignty and feeling ‘left behind’ by prosperous London. But as Harold Clarke, Matthew Goodwin and Paul Whiteley

show, survey data clearly reveal that the vote was linked to opposition to immigration. Indeed views on capital punishment

count far more in predicting whether someone is a Brexiteer than their class, income or beliefs about whether ‘the people’ should make decisions rather than politicians. The

consensus in the quantitative academic literature is that personal economic circumstances matter much less than cultural/psychological orientations in predicting immigration attitudes.

So we have a disconnect: the multivariate survey research finds that cultural attitudes correlate most strongly with views on immigration levels, with economics counting less. Yet the experimental research seems to indicate that people value skills more

than ethnicity in an immigrant. How can this be?

The mystery drops away when we consider that the experimental surveys ask about the properties of desirable

immigrants, not those of immigration. When people think of immigrants, they think of an individual, and assess them accordingly. When they think of immigration, they consider aggregate effects, which their minds treat as a separate question.

As I’ll show, people are sensitive to the skill level of the immigrant intake, but this is trumped by their concern for the cultural impact of a larger inflow.

To illustrate, I draw on data from a new Yougov-Birkbeck-Policy Exchange

survey of 1643 individuals from 5-6 November 2017, of which 1450 are of White British ethnicity. The question asked: ‘The government is considering its options for Britain’s immigration policy after Brexit. Currently Britain has net migration of 275,000

per year of which about half is European. After Brexit, European migration is expected to decline. Two options are on the table, which do you prefer?’

The sample was divided into nine equal groups for analysis. The first of nine groups saw the following set of options:

(a) Increase skilled immigration from outside Europe, keeping net migration at 275,000, raising the skilled share from 40% to 50%.

(b) Decrease skilled immigration from outside Europe, decreasing net migration from 275,000 to 125,000, lowering the skilled share from 40% to 20%.

(c) Don’t know.

People are being asked to trade off between a high-skill/high intake and low-skill/low-number intake option. 34% opted for option high skill/high intake, 30% for low skill/low intake, with 36% saying ‘don’t know’. This even holds when we ask about raising

numbers, as with:

(a) Increase skilled immigration from outside Europe, increasing net migration from 275,000 to 375,000, raising the skilled share from 40% to 60%.

(b) Decrease skilled immigration from outside Europe, decreasing net migration from 275,000 to 125,000, lowering the skilled share from 40% to 20%.

Result among those who answered are 31% for increase, 29% for decrease. In other words, 52% of those who answered the question backed the high skill, high immigration option. So far so good: a modest endorsement of the experimental literature, and of British

Future’s work, which shows that when the skill set is right, a (bare) majority of people will endorse current levels.

But now consider the next group’s set of choices. The only change in wording here is that I have replaced ‘outside Europe’ with ‘Africa and Asia’:

(a) Increase skilled immigration from Africa and Asia, keeping net migration at 275,000, raising the skilled share from 40% to 50%.

(b) Decrease skilled immigration from Africa and Asia, decreasing net migration from 275,000 to 125,000, lowering the skilled share from 40% to 20%.

(c) Don’t know.

Now just 18% are content with a high-skill/current migration level mix, 40% want a decrease with a lower skill mix, and 43% don’t know. That’s 69% in favour of a decrease in numbers and skills versus 31% for current levels with higher skills. Culture clearly

matters. Yet it turns out this is not the strongest cultural effect we find.

Consider the next set of options, based on ethnic population

projections:

(a) Increase immigration from outside Europe, keeping net migration at 275,000, raising the skilled share from 40% to 50%.

As a result, the White British share of the UK’s population will decline from 80% today to 58% in 2060.

(b) Decrease immigration from outside Europe, decreasing net migration from 275,000 to 125,000, lowering the skilled share from 40% to 20%.

As a result, the White British share of the UK’s population will decline from 80% today to 65% in 2060.

This time, the wording remains unchanged from that of the first group, but we draw attention to the impact higher numbers will have on long-term ethnic change. Rather than a – still substantial – shift from 80% to 65% White British by 2060 under the low

immigration option, we note that current immigration levels will mean a change from 80% to 58% White British by 2060, broadly in line with projections. With this choice in front of them, only 27% favour current levels with higher skills compared to 73% who

prefer a decrease even though this means a lower skill mix.

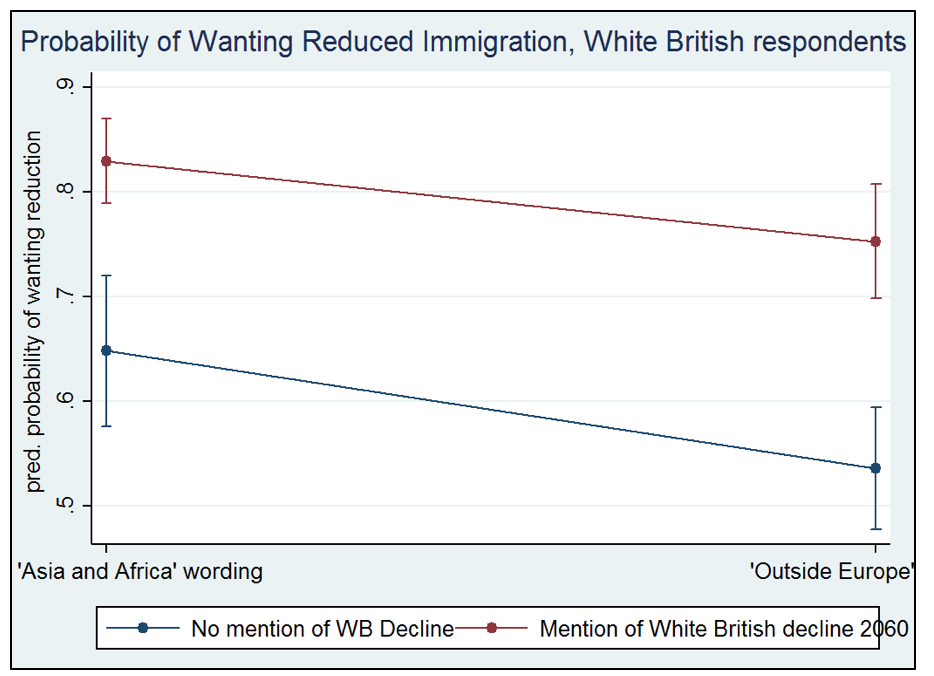

Across all nine variations, focusing on the 1450 White British respondents, we get the results in figure 1.

Figure 1.

![]()

This shows that a majority of White British respondents want reduced immigration even if skill levels fall. But when the question is worded, as in example 1, as new skilled immigrants coming from ‘outside Europe’ and when the decline in White British share

is not mentioned, it’s possible to get almost 45% of White Britons to back the high skill mix-with-high levels of immigration option. Mention ‘Asia and Africa’ as the source for new skilled immigrants and support slips ten points to 35%. More importantly,

mentioning the ethno-cultural impact of higher numbers on the long-term share of White Britons in the population drops support for current immigration levels by 17-22 points to just 18-25%.

We shouldn’t kid ourselves. The trends in figure 2, showing a link between net migration, news coverage, and the salience of immigration, is likely to continue in Britain. It’s a trend

James Dennison and his colleagues have noticed in most West European countries. This is largely because of its cultural and psychological impact, which immigration opponents are compelled by social norms to rationalise in economic terms. Focus groups are

especially susceptible to this. The Committee seem to have taken these rationales at face value, drawing distorted policy conclusions.

Figure 2.

Moving to a Canadian-style system of three-year immigration plans, as the report recommends, may be problematic for Britain. Canada’s latest three-year

migration plan for 2018-20 will welcome 330,000 immigrants per year, equivalent in UK terms to net migration of around 600,000 per annum, twice the current UK level. This has occurred because

norms of political discourse in English-speaking Canada are similar to those which obtained in Germany and Sweden prior to 2015 – in which it is deemed improper for politicians or editorial pages to advocate reducing immigration. Part of this,

note Emma Ambrose and Cas Mudde, stems from broadly-defined hate speech laws grounded in the 1971 Multiculturalism Act, which arguably encompass voicing opposition to immigration. This is clearly not the case in Britain, thus an attempt to transplant the

Canadian approach is likely to encounter considerable resistance.

Opposition to immigration is largely cultural and psychological. Policy options will therefore have to address this. Bracketing the question of numbers, I’ve argued

here and

here that one approach is to alter our current form of political communication to frame immigration to conservative voters as something which their ethnic group will ultimately absorb through intermarriage and

assimilation leaving the country little changed. Only by engaging with voters’ actual cultural-psychological concerns can we begin to approach the common ground the report’s authors seek. By contrast, the economic measures and procedures the Committee recommends

are unlikely to affect public opinion.

________

Note: a version of this article was originally published on

Policy Exchange.

About the Author

![]() Eric

Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London and author of

Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities (Penguin, October 2018).

Eric

Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London and author of

Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities (Penguin, October 2018).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.